Tour Guide to the Upstairs of the Abernethy-Shaw House

Upstairs at the Abernethy-Shaw House

The Professor's Studio

The Paintings

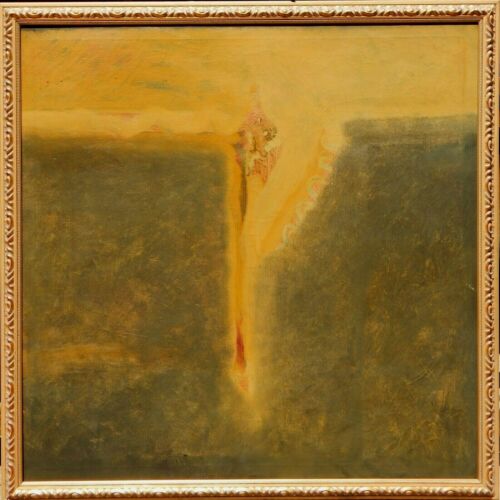

Details: "Sunset Triptych" by Pierre Graziani (1932-2020)

Large painting, 6 feet by 4 feet by the Corsican painter Pierre Graziani (1932-2020) A valley landscape is just visible through the clouds.

Pierre Graziani (born 1932 in Corsica) emerged as a significant figure in the French abstract art movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Originally named Piero, his adoption of the French version "Pierre" coincided with the beginning of his painting career, reflecting the cultural dynamics between his Corsican origins and the French artistic mainstream.

Graziani was prominently associated with Informal Abstraction and specifically the "Nuagisme" movement, as identified by critic Lucien Alvard in 1959. His distinctive approach within this movement was characterized by a rejection of defined forms, instead allowing color to dominate the entire canvas. This technique aligned him conceptually with certain American painters of the period, suggesting an early transatlantic dialogue in abstract expressionism. The Nuagisme movement

emerged during a crucial period in French abstract art, when Paris was grappling with the rising influence of American Abstract Expressionism. The term "Nuagisme" (derived from "nuage," meaning cloud) suggests an aesthetic preoccupation with ethereal, atmospheric effects that characterized certain strands of European abstraction in the 1950s.

The specific galleries where Graziani exhibited - such as Galerie Iris Clert and Galerie Daniel Cordier - were significant cultural institutions in post-war Paris. Iris Clert's gallery, in particular, was known for championing avant-garde artists and helping to establish new movements in contemporary art.

His later work shows a geographical and thematic expansion, particularly evident in exhibitions such as "Lake and desert of Turkana" (Nairobi National Museum, 1982) and "Sahara, des dunes célestes aux forêts nuages" (Chapelle de la Sorbonne, 2003), suggesting an evolution in his artistic concerns toward natural and environmental themes.

What's particularly significant about Graziani's career is his position within the broader context of post-war European abstraction. His association with artists like Benrath, Duvillier, and Laubiès places him within a crucial moment of transition in European modernism, while his distinctive approach to color and form suggests an independent artistic vision that transcended regional boundaries.

Details: Abstract Expressionist Landscape by Anton Weiss (1936-2019)

Anton Weiss's artistic trajectory exemplifies the complex interplay between European artistic traditions and American Abstract Expressionism in the post-war period. His personal journey—from war-torn Austria through Russian imprisonment to the vibrant streets of 1950s New York—mirrors the broader cultural migrations that shaped mid-century American modernism.

Weiss's formative experiences during World War II, including his imprisonment in a Russian concentration camp from age 10 to 13, profoundly influenced his artistic development. His early exposure to art came through his painter parents and his apprenticeship restoring cathedral frescoes in Austria—training that provided him with a strong foundation in traditional European techniques. This classical background would later inform his approach to Abstract Expressionism, creating a distinctive synthesis of European craftsmanship and American avant-garde practices.

The artist's crucial period of development occurred during his four-year residence in New York City (1956-1960), coinciding with Abstract Expressionism's ascendance to international prominence. His studies at the Art Students League, though ultimately unsatisfying, and subsequent training under Hans Hofmann proved transformative. Hofmann's influence was particularly significant, as his teachings emphasized the dynamic relationships between color, form, and spatial tension—elements that would become central to Weiss's mature work.

Weiss's artistic methodology evolved to incorporate both conventional and industrial tools, including homemade trowels, power drills, and palette knives. This experimental approach to materials and process aligned with Abstract Expressionism's emphasis on gesture and immediacy while reflecting his personal quest for artistic freedom. His technique of "opaque transparency," influenced by Richard Diebenkorn, involved complex layering of glazes to create depth and luminosity.

The artist's relationship with color reveals both intuitive and conceptual dimensions. His preference for earth tones and strategic use of bold colors like red, combined with his deliberate avoidance of purple (which he associated with darker emotional territories), suggests a highly developed color theory informed by both formal and psychological considerations.

Upon returning to Nashville in 1960, Weiss became a crucial figure in developing Tennessee's artistic infrastructure. His roles as department head at Watkins College of Art and Design and co-founder of both the Tennessee Art League and Tennessee Watercolor Society positioned him as a key mediator between national artistic trends and regional cultural development. This institutional work helped establish Nashville as a significant center for artistic innovation in the post-war South.

Details: "Tidsglimt" by Carlo Vandso Jensen

This work by a contemporary Danish artist presents a striking example of contemporary abstract painting. The composition is structured around a central white void or pathway that suggests architectural or web-like linear elements, surrounded by an explosive array of colors and gestural marks that appear to radiate outward toward an irregular, organic border. The color palette is particularly noteworthy, featuring deep blues, vibrant oranges, and crimson reds that create dynamic contrasts throughout the composition. These colors appear to have been applied through a combination of controlled and chance-based techniques, possibly involving fluid paint applications that have been manipulated to create marbling and flowing effects. The interaction between these colors produces areas of rich visual complexity, particularly where the pigments have merged or created transitional zones.

The painting's most distinctive formal element is its unconventional border structure - rather than conforming to a traditional rectangular format, the edges undulate in a biomorphic pattern that appears to respond to the internal energies of the composition. This decision to break from the conventional picture plane creates a dialogue between contained and uncontained elements within the work.

Details: "Seated Nude" by Duncan Grant (1885-1978)

This work exemplifies Duncan Grant's (1885-1978) characteristic approach to figurative painting, demonstrating his distinctive handling of the nude subject through expressive brushwork and a carefully modulated color palette. The painting displays the influence of Post-Impressionist techniques that Grant encountered during his early exposure to French modernism, particularly evident in the gestural application of paint and the use of greens and ochres in the background that create a dynamic spatial relationship with the figure.

The nude is rendered with a directness and physicality typical of Grant's mature style. The subject's pose suggests both classical precedents and modern informality, while the treatment of flesh tones through loose, visible brushstrokes reflects the artist's synthesis of traditional subject matter with contemporary painting techniques. The emerald green background functions both as spatial context and as an active compositional element, creating tension with the warmer flesh tones of the figure.

Duncan Grant's significance in 20th-century British art extends well beyond his individual works. As a central member of the Bloomsbury Group, he helped reshape British cultural life in the early 20th century. Born in Scotland and educated partly in Paris, Grant's artistic development was profoundly influenced by Post-Impressionism, particularly through his exposure to the work of Cézanne and Matisse. Roger Fry's landmark Post-Impressionist exhibitions of 1910 and 1912 proved pivotal in crystallizing Grant's artistic direction.

His long association with Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex, shared with Vanessa Bell, established a crucial center for modernist experimentation in Britain. Here, Grant produced paintings, textiles, and decorative arts that helped introduce modern European aesthetic principles into British domestic spaces. His work consistently demonstrated a commitment to sensual expression and formal innovation while maintaining connections to figurative tradition.

This particular nude study exemplifies Grant's ongoing engagement with the figure as a subject for modernist experimentation, combining formal innovation with careful observation. The painting's directness and lack of academic finish aligns with his broader project of updating traditional genres through modern technique.

Details: "Standing Nude" by Fausto Pirandello (1899-1975)

This work by Fausto Pirandello (1899-1975) presents a female figure in an interior setting, demonstrating his distinctive approach to modernist figurative painting. The composition's structural elements - the vertical architectural framing and geometric simplification of form - show influences of Cubist fragmentation while maintaining a strong sense of the figure's physical presence.

The semi-nude female figure is rendered with Pirandello's characteristic balance of anatomical understanding and modernist abstraction. The blue-dominated palette, with its subtle flesh tones and salmon pink accents, creates a psychological atmosphere typical of his interior scenes. His handling of paint varies between fluid and more structured passages, activating the surface while maintaining the figure's sculptural presence.

Pirandello's significance stems from his position within the Scuola Romana movement while maintaining an independent artistic vision. As the son of playwright Luigi Pirandello, he developed his artistic identity in dialogue with, yet distinct from, his father's cultural legacy. His work bridges traditional figurative painting and modernist experimentation, particularly in his treatment of the human figure as a vehicle for both formal and psychological exploration.

The work represents Pirandello's important contribution to post-war Italian painting, maintaining figurative commitment while engaging with modernist concerns.

Details: "Late Self Portrait" by E.E. Cummings (1894-1962)

E.E. Cummings (1894-1962) was as dedicated to visual art as he was to poetry, though this aspect of his creative life is less widely known. He painted throughout his adult life, producing thousands of works, including oils, watercolors, and drawings. His style was heavily influenced by post-impressionism and cubism, which he encountered during his time in Paris in the 1920s.

In his late self-portraits, like the one shown here, Cummings often portrayed himself with an intense, searching gaze and angular features that reflect both his modernist aesthetic and his interest in psychological revelation. The painterly surface, with its visible brushwork and textural qualities, suggests the influence of artists like Cézanne, whom Cummings greatly admired.The portrait manifests several characteristic elements of Cummings' visual style:

- A focus on geometric simplification of forms

- Strong emphasis on the psychological dimension of portraiture

- Rich surface texture that creates a dialogue between abstraction and representation

- Use of dramatic lighting to create emotional resonance

While his poetry is celebrated for its playful experimentation with form, typography, and linguistic conventions, his paintings often reveal a more somber, contemplative side. His late self-portraits, in particular, tend to possess a gravity and psychological depth that complements rather than mirrors the typically lighter tone of his verse.

This E.E. Cummings self-portrait was from the estate sale of Sherri Cavan, San Francisco Sociologist at San Franciso State University. She was also a sculptor and a well known listed artist from California. She was a published author of several well known books, including: Liquor License; An Ethnography of Bar Behavior (1966), Hippies of the Haight, (1972), 20th Century Gothic: America's Nixon (1979)

The Train Room

Hula Here!

If you encounter a Hula demonstration in this room feel free to ask Joan any questions you have about the practice of Hula which is both a dance form and a philosophy.

Here is a link to Information about Hula Culture in 1919

The Wicker Bedroom

The room's lighting design—combining period-appropriate table lamps with natural light from the windows—creates what lighting designers call "temporal atmospherics," enhancing both the historical ambiance and practical functionality of the space—a prime example of what we might call "lived heritage interpretation."

Details: "The Grapeseller" by William Perry (d. 1871)

"The Grapeseller" (c.1860) a large painting by William J. Perry showcases a young Roma vendor offering her wares to a resting traveler in a mountainous landscape. The painting's dramatic composition centers on the vendor's commanding presence - her black dress and red sash cutting a bold figure against a luminous sky that shifts from gold to turquoise. Perry masterfully captures a moment of rural commerce, with the vendor's confident stance and direct gaze suggesting both professional pride and cultural identity.

"The Grapeseller" (c.1860) a large painting by William J. Perry showcases a young Roma vendor offering her wares to a resting traveler in a mountainous landscape. The painting's dramatic composition centers on the vendor's commanding presence - her black dress and red sash cutting a bold figure against a luminous sky that shifts from gold to turquoise. Perry masterfully captures a moment of rural commerce, with the vendor's confident stance and direct gaze suggesting both professional pride and cultural identity.

What elevates this work beyond mere genre painting is Perry's sophisticated integration of narrative and technique. The triangular arrangement between vendor, seated traveler, and pack animal creates a visual harmony that also tells a story about rural economic life. His handling of light is particularly accomplished, using theatrical illumination to transform an everyday transaction into something more poetic without sacrificing its authenticity.

The painting's strengths lie in its dual nature - it satisfies Victorian artistic conventions while offering genuine insight into the mobile economies of rural life. Perry's attention to costume detail, his confident brushwork in the landscape, and his careful choreography of human interaction reveal an artist working at the height of his powers. This work, completed about a decade before his death in 1871, stands as a testament to mid-Victorian painting's ability to find beauty in the ordinary while documenting the social fabric of its time.

"The Grapeseller" (c.1860) a large painting by William J. Perry showcases a young Roma vendor offering her wares to a resting traveler in a mountainous landscape. The painting's dramatic composition centers on the vendor's commanding presence - her black dress and red sash cutting a bold figure against a luminous sky that shifts from gold to turquoise. Perry masterfully captures a moment of rural commerce, with the vendor's confident stance and direct gaze suggesting both professional pride and cultural identity.

"The Grapeseller" (c.1860) a large painting by William J. Perry showcases a young Roma vendor offering her wares to a resting traveler in a mountainous landscape. The painting's dramatic composition centers on the vendor's commanding presence - her black dress and red sash cutting a bold figure against a luminous sky that shifts from gold to turquoise. Perry masterfully captures a moment of rural commerce, with the vendor's confident stance and direct gaze suggesting both professional pride and cultural identity.Details: "The Studious Goatherd" by William Perry (d. 1871)

"The Studious Goatherd" (c.1860s) presents a fascinating inversion of typical Victorian pastoral scenes. Here, Perry captures a young shepherdess not in the expected pose of rustic labor, but in a moment of intellectual engagement - reading while tending her goat. The composition is both intimate and symbolic, with the figure in a vibrant red bodice leaning thoughtfully over her book, creating a striking contrast with the pastoral setting of wildflowers and misty landscape behind her.

The painting operates on multiple levels of social commentary. The very concept of a reading shepherdess challenges Victorian assumptions about rural literacy and female education. Perry's choice to depict his subject actively pursuing knowledge while performing her humble duties speaks to themes of self-improvement and the democratization of learning that were gaining momentum in the 1860s.

Technically, the work showcases Perry's mastery of atmospheric effects - the soft, clouded sky creates a contemplative mood, while the verdant foreground with its scattered wildflowers grounds the scene in tactile reality. The red of the shepherdess's clothing serves as both a compositional anchor and a symbol of vitality, drawing the eye to the central act of reading.

What makes this painting particularly significant is its subtle challenge to genre conventions. While maintaining the picturesque qualities expected of rural scenes, Perry infuses the work with deeper meaning about female agency and the pursuit of knowledge. The goat and shepherd's crook maintain the pastoral framework, but the book transforms this from a simple genre scene into a meditation on personal growth and the quiet revolution of rural education.

This painting pairs intriguingly with "The Grapeseller," showing Perry's range in depicting working women with dignity and complexity, each engaged in different forms of self-determination - one through commerce, the other through education.

Details: "Landscape" by Aldo Bahamante (b. 1963)

This evocative Spanish landscape represents an early work by Chilean artist Aldo Bahamonde (b. 1963), likely painted during his formative years in Madrid in the mid-1980s. The painting captures a quintessentially Spanish scene - a dusty road winding past terracotta-roofed buildings - rendered in a loose, impressionistic style that speaks to a young artist processing both his new environment and European artistic traditions.

Bahamonde's journey from Santiago to Madrid at age 21 marked the beginning of a significant artistic career. Under the mentorship of realist painter Guillermo Muñoz Vera, he would establish himself in the Spanish art world, eventually exhibiting at the Madrid Assembly and joining the prestigious Sammer Gallery group. This landscape, however, shows us an artist still finding his voice - experimenting with light, atmosphere, and brushwork in ways that differ from the more precise realism he would later embrace.

What makes this painting particularly fascinating is its quality of discovery. Through Bahamonde's outsider eyes, the Spanish countryside becomes a laboratory for exploring artistic possibilities. His handling of warm earth tones and hazy atmosphere suggests someone seeing Mediterranean light with fresh sensitivity, while his confident composition - structured around that meandering road - already hints at the technical facility that would characterize his mature work.

The painting thus stands as both a personal document of artistic development and a broader testament to the cross-cultural currents that have long enriched Spanish art. It captures a moment when a young Chilean artist, newly arrived in Europe, was working out his relationship to both his adopted landscape and the weight of artistic tradition he had crossed an ocean to engage with.

Details: "Conversation" Scandinavian School (ca. 1900)

This evocative Scandinavian painting from around 1900-1905 masterfully captures a moment of rural drama through both its psychological tension and atmospheric power. Against a spectacular twilight sky - rendered in luminous oranges and golds - three figures enact a scene of apparent moral complexity: two women have paused in conversation, their postures suggesting an intense exchange, while a male figure retreats into the deepening distance. The presence of a church spire on the horizon adds symbolic weight to what appears to be a moment of judgment or warning between the women, perhaps concerning the departing man.

The artist, working in either the Danish or Norwegian naturalist tradition, demonstrates remarkable skill in using landscape to amplify emotional content. The bare trees stand like silent witnesses, their stark forms echoing the confrontational nature of the scene, while the dramatic sunset creates both physical and metaphorical twilight - a moment of transition and revelation. The painting exemplifies the period's fascination with psychological realism and social dynamics in rural communities, where personal dramas played out against the backdrop of traditional values and modernizing society.

What makes this work particularly compelling is how it weaves together multiple threads of turn-of-the-century Scandinavian art: its technical mastery of light and atmosphere, its keen observation of rural life, and its subtle exploration of human relationships. Like a visual short story, it invites viewers to contemplate both the immediate drama of the scene and the broader social contexts that frame it, creating a work that is at once intimately personal and broadly representative of its time and place.

This evocative Scandinavian painting from around 1900-1905 masterfully captures a moment of rural drama through both its psychological tension and atmospheric power. Against a spectacular twilight sky - rendered in luminous oranges and golds - three figures enact a scene of apparent moral complexity: two women have paused in conversation, their postures suggesting an intense exchange, while a male figure retreats into the deepening distance. The presence of a church spire on the horizon adds symbolic weight to what appears to be a moment of judgment or warning between the women, perhaps concerning the departing man.

The artist, working in either the Danish or Norwegian naturalist tradition, demonstrates remarkable skill in using landscape to amplify emotional content. The bare trees stand like silent witnesses, their stark forms echoing the confrontational nature of the scene, while the dramatic sunset creates both physical and metaphorical twilight - a moment of transition and revelation. The painting exemplifies the period's fascination with psychological realism and social dynamics in rural communities, where personal dramas played out against the backdrop of traditional values and modernizing society.

What makes this work particularly compelling is how it weaves together multiple threads of turn-of-the-century Scandinavian art: its technical mastery of light and atmosphere, its keen observation of rural life, and its subtle exploration of human relationships. Like a visual short story, it invites viewers to contemplate both the immediate drama of the scene and the broader social contexts that frame it, creating a work that is at once intimately personal and broadly representative of its time and place.

Details: "Summer in the Garden" by Edouard Gaetan Charles Ansaloni (1878-1940s?)

Edouard Gaetan Charles Ansaloni was born at the end of the 19th century in Yzeure, a commune within the department of Allier, in central France. Ansaloni studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, under the tutelage of Jean-Leon Gerome, Benjamin Constant, and J.P. Laurens. Ansaloni is best known for his series of exhibitions between 1912 and 1939, which depicted views of Alsace, Auvergne, and Franche-Comte, all regions of Eastern France.

This painting is a number of views he did of a garden over time and changes of season. The figure of the gardener is sometimes clearly visible, and other times a shadowy presence in this series of paintings.

"Summer Garden with Hedge Wall" by Edouard Gaëtan Charles Ansaloni exemplifies the sophisticated integration of French academic training with early 20th-century approaches to light and color. Created during the artist's mature period, when he focused on regional subjects in eastern France, this canvas demonstrates Ansaloni's mastery of garden painting, a genre that held particular significance in French artistic tradition.

The composition is structured around a formal French garden design, with geometric flower beds radiating from a central axis and bounded by a substantial hedge wall that provides both spatial depth and tonal contrast. Ansaloni's academic training under masters like Gérôme and Laurens at the École des Beaux-Arts is evident in his precise handling of perspective and spatial relationships, while his brushwork shows a looser, more contemporary approach influenced by post-impressionist techniques.

Particularly noteworthy is Ansaloni's sophisticated treatment of vegetation, ranging from the carefully articulated flower beds with their mixed plantings to the imposing hedge wall that dominates the upper portion of the canvas. His palette demonstrates considerable subtlety in its handling of greens, from deep shadows within the hedge to sun-struck foliage, while touches of pink and red flowering plants provide rhythmic accents throughout the composition.

Details: "Classical Subject" Commercially Produced

The painting's technical execution demonstrates the adaptation of academic methods to commercial requirements. While the handling of flesh tones, drapery, and atmospheric perspective reflects formal artistic training, the efficiency of execution and standardized format point to studio production practices developed to serve the period's growing market for domestic art. The ornate gilt frame, featuring machine-pressed composition ornament rather than hand-carved decoration, further situates this work within the context of industrialized art manufacturing.

This piece represents a significant category of 19th-century cultural production: works that mediated between high artistic traditions and middle-class domestic environments. Through its careful balance of classical references, romantic sensibility, and controlled technical execution, the painting exemplifies how commercial artists and manufacturers adapted academic conventions to meet the cultural aspirations and economic means of bourgeois consumers. As such, it provides valuable insight into both the artistic practices and social dynamics of its period.

The work's preservation state and continued display demonstrate the enduring appeal of such paintings, while its material characteristics - from the standardized canvas to the mass-produced frame - document important developments in 19th-century art production and distribution methods. It stands as a telling artifact of how artistic traditions were transformed by and adapted to the requirements of an industrializing society and its expanding middle class.

This late 19th-century decorative painting exemplifies the intersection of academic artistic traditions with emerging commercial art production during a period of expanding middle-class consumption. The work presents a classical female figure in a romantic landscape, depicted pouring water from an urn - a composition that deliberately evokes both mythological references and allegorical meanings while remaining decoratively accessible.

The Hotel Suite

Details: "Marin County Hillside" by Ruth Malia

This painting beautifully captures the distinctive golden-brown palette of Northern California's Marin County landscape, rendered in a semi-abstract expressionist style characteristic of the mid-century period. The composition suggests a sun-bleached hillside, with the ochre and umber tones creating a sense of parched summer terrain so typical of the Bay Area's Mediterranean climate.

Malia's technique here is particularly interesting - she appears to have built up layers of paint to create a richly textured surface that mimics the rugged topography of Marin's coastal hills. The interplay between light and shadow, achieved through variations in yellow and deeper earth tones, evokes the way sunlight moves across the landscape throughout the day. The painterly, loose brushwork shows the influence of Abstract Expressionism while maintaining a connection to the physical landscape that grounds the work in the American naturalist tradition.

Details: "Swimmer" by Tano Festa (1938-1988)

This work exemplifies Tano Festa's (1938-1988) distinctive approach to Pop Art, filtered through a specifically Italian sensibility. As part of the Roman School of Piazza del Popolo, Festa emerged in the 1960s alongside artists like Mario Schifano and Franco Angeli, creating work that responded to both American Pop Art and Italy's rich artistic heritage.

This particular piece demonstrates Festa's characteristic style of simplified forms and flat areas of color. The composition features a figure in a bathing suit rendered in a minimalist manner, with turquoise accents against a flesh-toned form, set against a geometrically structured background. The addition of stylized floral elements in pastel hues creates a decorative element that feels both modern and reminiscent of classical Italian design motifs.

Festa's career was marked by his interesting position between tradition and modernity. While embracing Pop Art's contemporary visual language, he frequently referenced Italian art history, particularly Michelangelo and the Renaissance. This dual awareness made his work distinctly Italian while participating in the international Pop Art movement.

What's particularly interesting about this piece is how it reduces the human figure to essential shapes and colors, creating a kind of modernist odalisque that both references and reinvents classical themes through a Pop Art lens. The composition's simplified forms and clear color blocks reflect the influence of commercial printing techniques that were central to Pop Art's aesthetic, while maintaining a distinctly painterly quality.

This work appears to date from his mature period, when he had fully developed his signature style of combining Pop Art's bold simplicity with subtle references to Italy's artistic legacy.

This work exemplifies Tano Festa's (1938-1988) distinctive approach to Pop Art, filtered through a specifically Italian sensibility. As part of the Roman School of Piazza del Popolo, Festa emerged in the 1960s alongside artists like Mario Schifano and Franco Angeli, creating work that responded to both American Pop Art and Italy's rich artistic heritage.

Details: Two Lithographs by Guy Charon (1927-2021)

Guy Charon (1927-2021) was a French painter and lithographer who worked in Paris and was particularly known for his vibrant landscapes and still-lifes that captured the essence of French scenes, from coastal views to urban landscapes.

Charon was particularly celebrated for his mastery of lithography, a medium that allowed him to create works that balanced sophisticated color relationships with accessible imagery. His work often featured interior-exterior views - a glimpse through a window to a garden or seaside scene beyond - with floral arrangements in the foreground serving as a compositional bridge between these spaces.

The two lithographs you've shared are quintessential examples of his mature style. They demonstrate his characteristic approach: bold color harmonies, simplified yet expressive forms, and a sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships. His work often played with the relationship between decorative and naturalistic elements, creating scenes that feel both observed and imaginatively transformed.

What makes Charon's work particularly interesting is how it sits at the intersection of modernist abstraction and traditional French landscape painting. His lithographs were popular during a period when France was experiencing both economic growth and cultural transformation, and his accessible yet sophisticated aesthetic appealed to a growing middle-class audience interested in contemporary art.

Charon's long career (spanning over six decades) allowed him to develop a distinctive visual language that remained remarkably consistent while continuously evolving in subtle ways. His work contributed significantly to keeping the tradition of French lithography vital during the latter half of the 20th century.

These particular pieces display his characteristic ability to create depth through layered planes of color, using the lithographic medium to achieve both boldness and subtlety in his color relationships. They're excellent examples of why his work became popular with collectors who appreciated both their decorative appeal and their technical sophistication.

What makes Charon's work particularly interesting is how it sits at the intersection of modernist abstraction and traditional French landscape painting. His lithographs were popular during a period when France was experiencing both economic growth and cultural transformation, and his accessible yet sophisticated aesthetic appealed to a growing middle-class audience interested in contemporary art.

.jpg)

%20midcentury%20cubist.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment